Cloud load balancing is how cloud computing keeps its promises of elasticity, availability and speed. Cloud platforms pool compute, storage, and networking resources, then deliver them as services over the internet. But without careful traffic distribution, that flexibility quickly collapses into contention and outages.

As per the latest report by Mordor Intelligence, cloud computing spending accelerates toward an estimated $2.26 trillion by 2030.

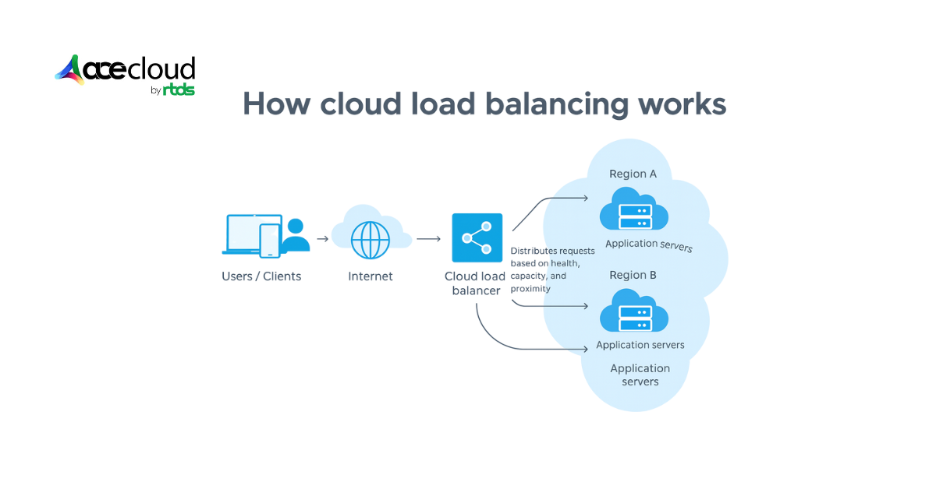

Load balancers sit between users and resources, spreading requests across servers, zones and sometimes regions, based on health, capacity and proximity. They prevent individual nodes from becoming hot spots, allow rolling releases without visible downtime and turn collections of commodity instances into a single, reliable service.

When demand spikes, cloud load balancing works with autoscaling, CDNs and reverse proxies, so applications degrade gracefully instead of failing abruptly. This article examines what load balancing in cloud computing is, the main types and how to use them to design resilient architectures.

What is Cloud Load Balancing?

It is the process of intelligently distributing traffic, workloads and client requests across multiple servers in a cloud environment. By ensuring each resource handles only as much as it can efficiently manage, it prevents any single resource from being overload and avoids idle capacity.

Load balancing helps organizations handle cloud-based workloads more effectively, improving application performance, boosting reliability, reducing downtime and keeping latency low.

How Cloud Load Balancing Operates?

A cloud load balancer distributes incoming traffic across multiple backend resources (like virtual machines, containers, or serverless functions) to improve availability, performance, and scalability.

Here’s how it typically works:

1. Client request

A user hits your application via a public IP or DNS name (e.g., api.example.com). That address points to the load balancer, not directly to any server.

2. Listener & protocol handling

The load balancer has listeners for specific ports and protocols (HTTP/HTTPS/TCP). It terminates the client connection at this point, often handling TLS/SSL decryption for HTTPS (“SSL termination”).

3. Health checks

The load balancer regularly probes each backend (e.g., GET /health) to check if it’s alive and healthy. Unhealthy instances are temporarily removed from rotation.

4. Routing & balancing algorithm

For each incoming request, it chooses a backend using algorithms like:

- Round robin – Cycle through servers.

- Least connections – Pick server with fewest open connections.

- IP/hash-based – Keep a client “sticky” to the same server.

For HTTP(S), it may also do path-based or host-based routing (e.g., /API to one service, /images to another).

5. Forwarding to backends

The load balancer forwards the request to the selected backend in a private network, rewrites headers (like X-Forwarded-For) and waits for the response.

6. Returning the response

The response is sent back to the client over the original connection, so the client sees a single endpoint even though many servers might be involved.

7. Elastic scaling & global reach

In cloud environments, backends can automatically scale up/down, and global load balancers can route users to the nearest region, improving latency and resilience.

What are the Benefits of Load Balancing in Cloud Computing?

Load balancing plays an important role in cloud computing and offers several benefits. Some of the top ones are the following:

Improved performance

Automatic distribution across multiple resources lets your applications absorb traffic spikes while preventing hotspots, which stabilizes throughput and preserves low response times during peak demand.

Greater reliability

Hosting services across several cloud hubs allows routing around localized failures and isolates the blast radius, which maintains availability when zones degrade or components crash.

Reduced costs

Software-based load balancing removes purchase and maintenance costs for on-premises appliances and support contracts, while managed services reduce rack space, power and spare capacity requirements.

Reduced latency

In internet-facing architectures, this is often combined with anycast IPs or CDN edge nodes so traffic terminates close to users before being forwarded to backends.

Easier automation

Near real-time insights from cloud load balancers enable automated decisions, and predictive analytics highlight emerging bottlenecks early to trigger scaling or routing adjustments.

Faster recovery

During network emergencies or regional events, providers redirect traffic to healthy regions, which preserves continuity and keeps incidents or maintenance windows largely invisible to customers.

Improved flexibility

Routing traffic to alternative servers supports patching, updates, remediation or production testing while preserving user experience, which accelerates delivery and reduces change risk.

Better security

Distributing requests across many servers helps absorb volumetric spikes and can reduce the impact of some DDoS patterns when combined with WAFs, rate limiting and upstream DDoS protection, while rerouting away from saturated endpoints maintains service quality under stress.

Seamless scalability

Integration with autoscaling adds or removes capacity in response to demand; therefore, applications expand efficiently during peaks and contracts during quieter periods without manual intervention.

Continuous health checks

Many managed DNS services and application load balancers run periodic health checks on upstream servers, and unhealthy targets are quickly removed from rotation to prevent cascading failures.

You may also like:

- What Is Network Security? Definition, Types, and Best Practices

- Public Cloud- The Way You Do Efficient Computing

What are the Different Types of Load Balancing?

You should classify load balancing by deployment model and protocol layer to match performance, resilience and cost.

Based on configurations

Load balancers can be classified by how they are deployed and operated. Traffic distribution may be delivered by hardware appliances, software on general-purpose servers, or cloud-hosted configurations.

Software load balancers

Software load balancers run as applications or components on standard servers. This approach provides flexibility and fits diverse environments without proprietary hardware. In a simple setup, the client selects the first server in a list and sends the request.

If failures persist after a configured number of retries, that server is marked unavailable and the next target is used. This remains one of the most cost-effective ways to implement load balancing, especially on-premises or in self-managed environments.

Common examples include HAProxy, Nginx and Envoy.

Hardware load balancers

Hardware load balancers are physical appliances that distribute traffic across backend servers. Often called Layer 4–7 routers, they handle HTTP, HTTPS, TCP and UDP at high throughput.

These devices deliver strong performance but are expensive and less flexible than software options. When a server fails health checks or stops responding, the appliance immediately halts traffic to that node. Many providers place hardware load balancers at the edge, then rely on internal software load balancers behind the firewall.

Virtual load balancers

A virtual load balancer is implemented as a VM or software instance in virtualized environments such as VMware, Hyper-V or KVM. Incoming traffic is distributed across multiple resources to improve utilization, reduce response times and prevent overload while retaining software-level agility.

Virtual load balancers are common in private clouds and transitional environments migrating from hardware to fully managed load balancing.

Managed load balancing vs self-managed

For many teams, the key choice is between self-managed load balancing and managed load balancing.

- Self-managed load balancing: You deploy and operate Nginx, HAProxy, Envoy or similar components yourself, handling upgrades, scaling, monitoring and high availability.

- Managed load balancing: Cloud providers offer load balancers as a service. You configure listeners, target groups and health checks, while the provider runs and scales the control and data plane.

Managed load balancing reduces operational overhead and accelerates delivery but can increase dependence on a specific cloud and constrain advanced customization. Self-managed load balancers offer more control and portability at the cost of more engineering effort.

Based on functions

Load balancers are also categorized by how they process and route traffic across network layers to ensure efficient handling and high availability.

Layer 4 (L4) load balancer/ network load balancer

- Scope: Operates at the transport layer for TCP or UDP

- Decision basis: Uses IP addresses and ports rather than inspecting payloads

- Performance: Processes packets quickly because content inspection is avoided

- Additional capability: Performs basic NAT to mask internal server addresses

Layer 7 (L7) load balancer/ application load balancer

- Scope: Operates at the application layer for HTTP or HTTPS

- Decision basis: Routes by URLs, headers or cookies for content-aware control

- Advanced behaviors: Enables intelligent routing and policy-driven decisions

- Security offload: Terminates SSL to centralize certificate management

Global server load balancer (GSLB)

GSLB distributes traffic across multiple sites or regions rather than a single data center. Proximity, health and geography are considered to direct users to the best location, improving resilience and experience for globally distributed applications.

DNS load balancing

DNS load balancing distributes traffic by returning different IP addresses for the same hostname, based on policy, health or geography. It is less granular than L4/L7 but is useful for:

- Directing users to different regions.

- Steering traffic between providers in multi-cloud architectures.

- Implementing simple active-active or active-passive failover.

External vs internal load balancing

- External load balancers expose services to the internet, handling user traffic, enforcing TLS and integrating with CDNs and WAFs.

- Internal load balancers operate inside VPCs or VNets to balance east-west traffic between microservices, databases or internal APIs.

Both patterns are important in cloud architecture. Many systems use external load balancers at the edge and internal load balancers for service-to-service communication.

How Cloud Load Balancers Decide Where to Send Traffic?

It uses load balancing algorithms to decide which backend should receive each request or connection. Choosing the right approach is essential for performance and stability.

Round robin

Send requests to servers in a fixed rotation, equalizing distribution without performance measurements. At the DNS layer, an authoritative nameserver cycles through A records to spread client connections.

Weighted round robin

Apply weights so higher-capacity servers receive proportionally more turns in the rotation. Configure weighting in DNS records or within the load balancer, depending on deployment.

IP hash

Generate a hash from source and destination IP addresses, then map it to a backend. This provides simple session affinity and keeps repeat clients anchored without inspecting application payloads.

Least connection

Route new requests to servers with the fewest active connections at that moment. This method assumes that each connection requires roughly equal processing effort.

Weighted least connection

Assign capacity weights, letting higher-capacity servers take a larger share of new connections. Weights can reflect CPU, memory or instance class to keep utilization balanced.

Weighted response time

Combine average response time with current connection counts to choose the next target. Favor faster responders to improve perceived performance during spikes and noisy-neighbor events.

Resource based

Distribute traffic using real-time resource availability reported by lightweight agents on each server. The load balancer queries agents for CPU and memory headroom before routing, which reduces overcommit risk.

Accelerate Reliability with AceCloud’s Load Balancing

Cloud load balancing turns your architecture into a predictable, resilient platform that meets latency targets and uptime commitments at scale. With AceCloud, you implement managed load balancing that integrates health checks, autoscaling and multi-region routing to reduce downtime risk.

Our experts help you to align load balancing in cloud computing with existing architecture, then right-size policies for latency, cost and failover. You can evaluate cloud load balancer types against traffic patterns, compliance needs and budgets, then adopt the approach that fits best.

Start a no-cost consultation to map workload priorities, estimate performance gains and align costs with managed load balancing on AceCloud. Schedule your architecture review now and turn traffic spikes into steady throughput with a production-ready plan and clear ownership assignments.

Suggested read: Everything You Need To Know About Network Infrastructure Security

Frequently Asked Questions:

Cloud load balancing distributes network and application traffic across multiple cloud resources to prevent overload and improve performance, reliability and scalability.

Primary types include L4 network balancers, L7 application balancers, global server load balancers, DNS traffic steering, plus external and internal variants for internet and service traffic.

Managed load balancing means your cloud provider operates the service. You configure listeners, rules and target groups while the provider handles scaling, patching and availability.

Choose L7 when routing paths, hostnames, headers or cookies, and when you need TLS termination, WAF integration and application level observability. Use L4 when you require simple distribution, very low overhead and support for non-HTTP or TCP and UDP workloads where deep inspection is unnecessary.

A reverse proxy forwards client requests to backend servers and centralizes functions like TLS termination, caching and header normalization for downstream applications. A load balancer is a specialized reverse proxy that applies algorithms, health checks and policies to spread traffic across many backends and avoid single server overload.

Even modest applications gain zero downtime deployments, smoother scaling and protection against local failures, and adopting cloud load balancing early reduces migration risk as traffic and expectations grow.